The Red River Brief (The Wrong Brother): Part IV

But how did you even find Alick de Montmorency, weirdo?

It began with a challenge from a friend: find the connection between Shreveport, Louisiana and the JFK assassination plot. He knew of my passions for history, for the complexities of history, and for the illusions of history that the victors present: the tidying up of their own atrocities which are often worse than those they are fighting to prohibit. My friend had heard rumors through the years about certain connections to the murder in Dallas; he also knew that I was competitive, relentless, and would not quit at the dead ends of several thousand rabbit holes. It was as though another fuse to a powder keg had been lit.

To quote (and honor) Captain Benjamin L. Willard, “I took the mission. What the hell else was I gonna do?"

Admittedly, my research began with the presumption that it would be impossible for me to ever discover something related to the case that had not already been presented. But I have always been a bit of a contrarian so I decided to attempt a new route up the Mt. Everest of unsolved mysteries, without a Sherpa as my guide nor an ample supply of oxygen. My drive would be fueled by Socratic dialogue in my head and the scientific method: question an element of the assassination, do background research, construct an hypothesis for that particular element, test the hypothesis with pertinent facts, analyze the data, then share with others.

Share with whom? The single gunman experts or the massive conspiracy experts who have never been able to deliver a definitive resolution?

Socratic dialogue. I pondered my own studies of Philosophy in college; my obsessions leaned in the direction of providing premises/theorems through the application of Aristotelian logic to reach fact-driven conclusions. The only two ‘A’ grades I ever received in my major were for classes entitled “Philosophy of Literature” and “Philosophy of Logic.” I admit that now as much for braggadocio as humility. Whatever path or route I was going to take with this endeavor had to be driven by constant questioning of researched material lest I fall into the same traps that I have accused my now-colleagues and predecessors of doing. I had to illuminate facts without dilution and, frankly, that seemed like an impossible task.

Where to begin? The Warren Commission Report, subtitled The Official Report on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy? Any of the thousands of books written on the subject from the germane to the perverse? I spent a lot of time pacing. Walking. The circulation does one’s brain good. And so I would take long strolls in the Louisiana heat during a pandemic, fighting off mosquitos and picking stickers from the brush out of my socks, sans shirt at times to avoid the risk of an irritative heat rash from a sweaty fabric at the expense of a sunburn.

I was approached by an elderly woman on one of these occasions. She had passed me in her minivan on a desolate road in Shreveport, then turned around and slowed to a stop. Her passenger window lowered as I extracted my headphones from my ears. My initial thought was that she needed directions; guessing her age to be well over 80, I assumed her mapping skills were pedestrian at best.

“May I help you, Ma’am” I asked.

“Are you doing okay?” she replied. “I have a sandwich here if you’re hungry.”

Now, this was either the sweetest offer that any stranger has ever made to me when not under the influence of drugs or alcohol, or I was about to be drugged and kidnapped.

“No thank you, Ma’am,” I said. “Nice of you to stop.”

“Well you look hungry,” she said. “Do you have a place to stay tonight?”

I was not being propositioned by an old lady. She thought I was a bum wandering aimlessly down a street on which she had never seen a single soul stroll before! Who else would possibly make the choice to take a walk in this heat?

My chuckles subsided soon after she drove away when I realized that my appearance inspired a compete stranger to assume that I was indigent. Soon thereafter, I began to analyze the event and it led to the first mindset breakthrough for the course of study for which I had been challenged.

Misperception is rampant without even the most cursory of investigations into the most simple of occurrences. And when the subject matter is of critical importance, of critical significance, and has massive repercussions, there is an exponential—almost infinite—degree to which every misperception is amplified. Maybe my investigation needed to include a mathematical approach to match the philosophical approach. I thought about that on the rest of my walk. I thought about it in the refreshing shower when I did not even bother to turn the knob for the hot water. And I asked myself a simple question that would be the basis for my research: what are all of these JFK assassination investigators missing?

My mindset may have been in order at the onset, but my studious discipline was not. I haphazardly entered words into search engines that regurgitated the same results that every other JFK plot dilettante would have found. Like those same dreaded massive plot disciples, I would latch myself to a superfluous name of someone who may have once driven past Lee Harvey Oswald’s home in New Orleans as though it were the Holy Grail. It was wholly engrossing, yet frustrating. I was making mistakes that had been made by thousands of others. I was not special. Those first few late nights were humbling, so I decided to take a study break.

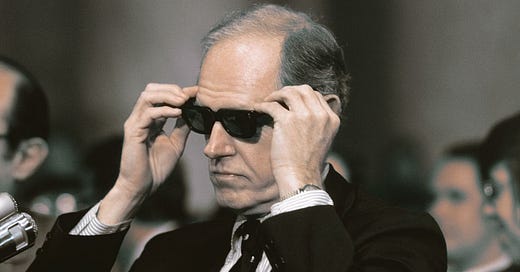

I would not be taking a walk, or getting a massage, or even eating a half gallon of chocolate ice cream in one sitting (which, as people will attest, I can do). Instead, I opted to watch some of the videos from the United States Senate Watergate Committee hearings of 1973 because that is what a normal person would do. It was approximately 1:30AM and for the next nine hours I would watch the entire testimony of E. Howard Hunt. And it would change my life forever.

Mr. Hunt delivered the greatest performance I have ever seen. Far better than Olivier or Brando. Far superior. And I became obsessed. I was vaguely familiar with Mr. Hunt from prior historical interests, but I had never delved into any specifics of his life, his past, or his apparent involvement in nearly every significant clandestine operation performed by the Central Intelligence Agency over the course of two decades.

He was involved with Operation PBSuccess for the overthrow of Jacobo Árbenz, the President of Guatemala. Here is one of Hunt’s quotes about the mission: "What we wanted to do was to have a terror campaign to terrify Árbenz particularly, to terrify his troops, much as the German Stuka bombers terrified the population of Holland, Belgium, and Poland.”

This reference to Nazism should be evaluated in regard to earlier near-suppositions in this series.

Hunt was involved as a prominent CIA planner for the Bay of Pigs Invasion of Cuba. He was involved with first the bugging, then the burglary, of the office for the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate office building. And Hunt was in Dallas on November 22, 1963.

I watched him for nine hours. I observed his mannerisms, his style of speech, and his eyes. For much of the hearing, Hunt wore Ray Ban Wayfarer sunglasses. At other times he would wear spectacles. My impression was that he was doing backstage costume changes—but in plain sight—to throw off his interrogators, the same for the millions of people watching the televised proceedings at home. Hunt would place his hand over the microphone at his table and confer with his attorney at annoyingly inopportune moments for the committee members. He was brilliant and I was upset at myself for not developing this fascination with him decades earlier.

For the next several weeks I studied E. Howard Hunt more than I had studied a single historical figure in my entire life. I felt oddly drawn to him, not as though I knew him well but as if we were connected somehow. It is the same feeling I experienced when I saw a photograph of Alick for the first time. Oddly enough, it was because of Hunt that I found that first photograph of Alick; the first of many coincidences that would accumulate in my research to create mathematical probabilities.

I questioned my pursuit of Hunt. Why was he so compelling? Why would anyone believe that a lifelong, devoted intelligence agent would actually tell the truth at a congressional hearing?

And why, many years later, would E. Howard Hunt sue The Spotlight magazine for libel in relation to an article alleging his involvement in the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Post-Watergate opinion columns frequently marginalized Hunt as some sort of bumbling, ineffective agent throughout his career. Were this to be the actual case and an accurate depiction, why was he repeatedly chosen for the agency’s toughest assignments imaginable? Government-backed disinformation campaigns have been managed by intelligence agencies since time immemorial.. In fact, it was actually easier to monitor these campaigns prior to the development of the worldwide web. The connection between the influence of the CIA-created North American Newspaper Alliance, and its connection to the JFK plot, has already been noted.

And Hunt was not going to be a turned into a disposable patsy like Oswald. As a master spy, he would lie until the end and never reveal the truth. The tradecraft for intelligence operatives can be encapsulated in one word: lie.

Here is the basic timeline for Hunt’s lawsuit against The Spotlight:

(1) An article by former CIA agent Victor Marchetti on 8/14/78 in The Spotlight accused E. Howard Hunt of involvement in the JFK plot based on a disputed, internal CIA memo. This was clearly a misdirection campaign by the CIA to push possible public interest away from former President Nixon and future Vice President Bush.

(2) Hunt sued The Spotlight for libel and a jury awarded him $650,000 in 1981.

(3) The verdict in Hunt’s favor was overturned in 1983 on appeal due to improper jury instructions.

(4) After a second trial in 1985, the jury overturned the first decision in favor of The Spotlight and its parent company, Liberty Lobby.

Hunt’s trial loss is the only adjudicated court decision (verdict) in the history of the United States that favorably ties any person directly to the assassination of President Kennedy, yet is an afterthought for the vast majority of expert researchers in the field. This made no sense to me. Placing my obsession with Hunt aside, I had to put myself into the seat of a jury member.

I read the trial transcript, but something emerged as a head-scratcher or, as gamblers who lose on a bizarre play during a game are oft to lament, a don’t-make-senser. Why would Hunt even bother to sue a far right fringe publication like The Spotlight that catered to such a nominally-sized audience? He could have just let it go as yet another unfounded Kennedy assassination rumor.

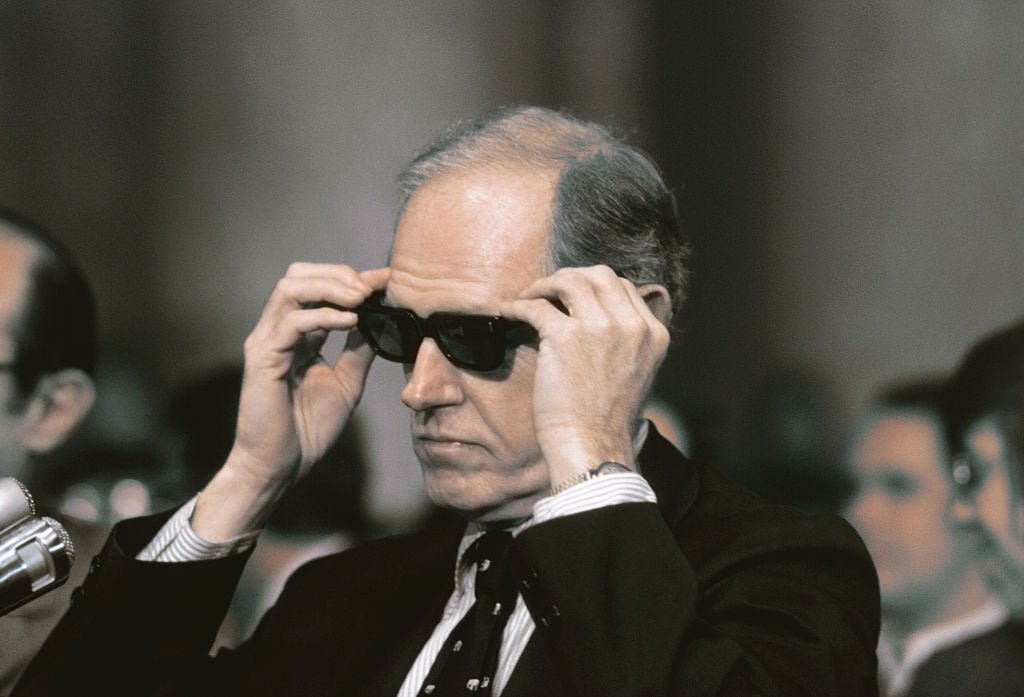

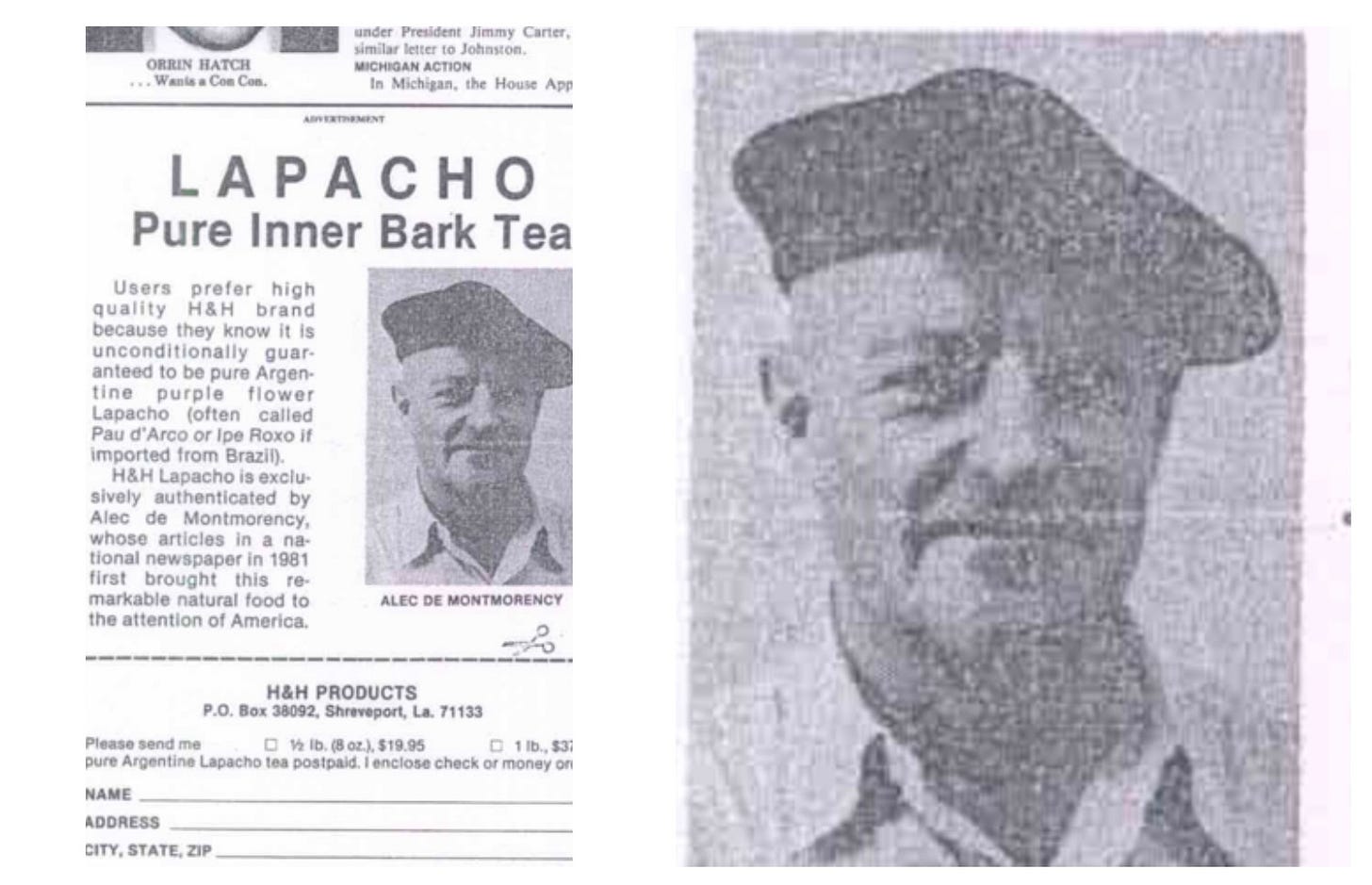

It was around 2:30AM on a weeknight (Summer 2021) that I was lying in bed scrolling through articles from The Spotlight about Hunt’s lawsuit. Because I was doing this research on my phone instead of my laptop, it was necessary to use my fingers on the screen to expand and contract the archived magazine images so that I could access the entirety of the articles. I was also contending with an overall sloppiness caused by weariness and fatigue. And, frankly, I had made the decision that these were the last data points I would collect about Mr. Hunt before moving on to yet another alleged perpetrator, accomplice, or abettor.

In the preceding weeks and months, I had gone down—as mentioned previously—thousands of rabbit holes. Thousands might be underestimating the actual total. But nothing in my research was unique or different. None of my findings had been original and I just spent weeks of investigative work infatuated with E. Howard Hunt. And how could any of my findings be original? None of my conclusions could have been drawn from anything but the previous work of others!

My fingers slipped on the screen and, in doing so, the page for The Spotlight article I was reading drifted down to an advertisement in the lower left corner. Typically, when I am reading something in a magazine or newspaper—whether online or in my hands—I do not notice the ads. I understand that they are there, but they serve only as a minor distraction. Tire ads, bra ads, sporting goods, beer. They are all the same. My interest is in the story, the editorial, the report from the hockey game last night. Not the advertisements for diet pills.

But this time, because I was on my phone and my eyes were directed to a small field of vision for the screen, I saw a photo that would change my life forever. One photo discovered chiefly by clumsy fingers, one that I might never have noticed on my laptop or if holding a tangible copy of this particular edition of The Spotlight. But there it was. Rather, there he was. I do not know how many professional journalists or assassination experts use profanity in their treatises, but my reaction to the photo was “Will you look at this fucking guy?”

I stared at him intently. He looked like someone from a movie. Ruggedly handsome, wearing a beret tilted slightly atop his head. My first thought was that he must be a soldier of fortune, a mercenary recruiting for action in Africa or South America or some other exotic locale. And he looked vaguely familiar. I stared at his face without bothering to notice the accompanying text. It was blurry to me at this point of the night. There was just something about this man’s face that evoked a deep understanding for me.

“I know I’ve seen this man before,” I thought. “But where?”

And let me state that, at this point of my exhaustive research, I had reached a rather frustrating point. My commitment to the original challenge was not waning with any sort of aggressive momentum to a recusal, but I was questioning whether my time commitment was worth it.

But then, suddenly, I found a rabbit.

My eyes finally moved to the text for the ad. This gentleman was selling Lapacho Bark Tea from the Bariloche region of Argentina. An herbal remedy. A health food product. I had not heard of this particular tea, but the ad itself looked like the typical offering from a huckster looking to overcharge fountain of youth seekers and habitual dieters that one would happen upon in a publication such as The Spotlight or The Weekly World News.

This was 1985. There was no internet. If you found a product you liked in the back of a magazine, you either called a number to order it or filled out your name and address on a form then mailed it with a check to the business address. It feels so archaic to even have to type that explanatory description nearly four decades on, but it is geared for younger readers who might not fathom that there was actually a time without immediate delivery and consumption.

The mailing address on the advertisement for Lapacho Bark Tree was located in Shreveport, Louisiana.

Goosebumps. Chills. I felt like I was going to vomit. I sat up, got out of bed, and grabbed my laptop. I emailed my friend. I texted him about forty times, too. These were the ramblings of an exhausted fool who had somehow stumbled upon, with the most bizarre luck imaginable, a connection to Shreveport. But what did this prove in a tangible, direct manner to the assassination itself?

Nothing.

Yet, it was a start. It was a launching point. I looked at the ad again. In my haste and excitement after seeing “Shreveport” in the ad, I had neglected to notice this man’s name.

It was Alick de Montmorency.

A rather fascinating name to go along with a rather fascinating face below a beret for someone importing tea from South America to a medium-sized city in Northwest Louisiana through an advertisement in a magazine being sued by a prolific former CIA operative who was one of the Watergate burglars. How was I supposed to make even nominal sense of this?

But it all did make sense after a most circuitous journey of dedicated research and investigation prompted by one lucky slip of my fingers. Happening upon Alick de Montmorency was a bit of a miracle; I had never heard of him before, but he sure did look familiar. And he was mysterious. There was a twinkle of mischief in his eyes discernible through the grainy, black and white advertisement that had been scanned by, undoubtedly, one of the earliest scanners ever produced.

In my eyes, he was now conjoined with E. Howard Hunt. I had no proof of a relationship between the two, and I had no factual evidence about Alick de Montmorency, but I had the providence of this fortuitous discovery.

And at this particular juncture it was more than enough to inspire me to continue.

Then I remembered where I had seen him before: he was the man photographed outside of the Soviet Embassy in Mexico City two months before JFK was assassinated, some 22 years before this Louisiana-based advertisement in The Spotlight. More goosebumps. More chills. But even in the excitement of this victory, I maintained an investigator’s discipline and questioned myself:

How and why am I the only person in history without prior knowledge to have figured this out?